The political temperature in West Bengal has reached a boiling point ahead of the 2026 Assembly elections, with the Election Commission of India’s (ECI) Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls sparking a fierce confrontation between the state government and central authorities. Following the publication of a draft roll that deleted over 58 lakh names, Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee has issued a combative call to arms, urging the women of Bengal to turn their domestic implements into tools of resistance against alleged disenfranchisement.

The Call to Arms: Kitchen Tools as Weapons of Resistance

In a fiery address at a rally in Krishnagar, Mamata Banerjee framed the SIR process not as a routine administrative update, but as a direct assault on the rights of “mothers and sisters”. Responding to fears that genuine voters might be struck off the lists, she invoked the symbolism of the kitchen to mobilise her core support base.

“Mothers and sisters, if your names are removed, you have the tools—the very tools you use in the kitchen,” Banerjee declared, specifically naming “khunti” (ladles) and “belan” (rolling pins) as instruments of defence. She warned that “police from Delhi” might be brought in to intimidate voters during the elections but asserted that women would lead the fight with men standing in support. Her rhetoric underscores the Trinamool Congress’s (TMC) strategy to treat the SIR as a battle for Bengali identity and survival, explicitly stating she would not let rights be “snatched in the name of SIR”.

The “Shocking” Numbers: 58 Lakh Deletions

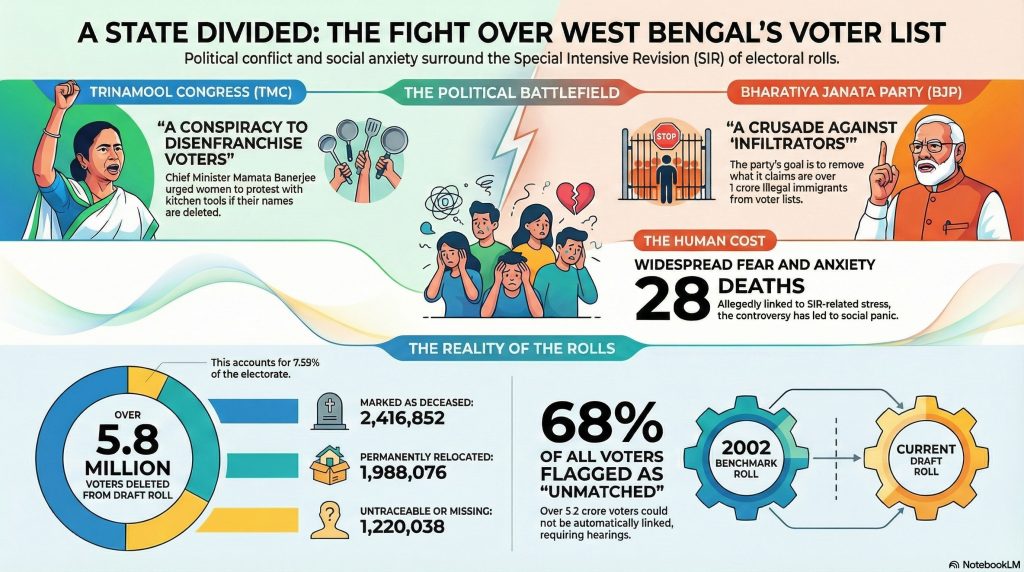

The Chief Minister’s warning comes in the wake of the ECI publishing the draft electoral rolls on 16 December 2025, which revealed the deletion of 5,820,899 voters—approximately 7.59% of the electorate. The ECI justified these deletions citing specific reasons:

• 24.1 lakh were marked as deceased.

• 19.8 lakh were categorised as permanently shifted.

• 12.2 lakh were deemed missing or untraceable.

While the ECI maintains this is an exercise to ensure the “purity” of the rolls by removing dead and duplicate entries, the scale of the deletions has triggered panic. The anxiety hit close to home for the Chief Minister when it was revealed that 45,000 voters were deleted from her own constituency, Bhabanipur, representing nearly 22% of its electorate. The TMC has since mobilised booth-level agents to conduct physical verification of every deleted name, fearing “silent rigging”.

The 2002 Benchmark: A Bureaucratic Nightmare

The root of the panic lies in the ECI’s decision to use the 2002 electoral roll as the “benchmark” for verification. Voters are required to link their current registration to their own or their ancestors’ names in the 2002 list to prove their “legacy”.

The data reveals a massive administrative gap: only 32% of current voters have successfully “matched” with the 2002 records. This leaves a staggering 68% (over 5.2 crore voters) classified as “Unmatched”. These individuals now face the prospect of formal notices and hearings where they must produce “legacy documents” dating back decades. Critics argue this requirement disproportionately affects women, the poor, and migrant communities who often lack historical paperwork, effectively placing a “citizenship-like burden of proof” on them.

Ghost Voters vs. NRC Fears

The political narrative is sharply divided. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has supported the SIR, describing it as a necessary step to identify and remove “one crore Rohingyas/Bangladeshis” allegedly brought in by the TMC as a vote bank. In contrast, Mamata Banerjee has likened the SIR to a prelude to the National Register of Citizens (NRC), warning of detention camps and deportation.

The fear is palpable on the ground. Reports indicate that panic over the SIR and the demand for 2002-era documents has led to suicides and caused hundreds of undocumented migrants to flee back to Bangladesh. The draft roll did identify around 1.8 lakh “ghost” or “fake” voters, lending some credence to the need for revision, yet the sheer volume of “unmatched” citizens suggests a systemic crisis rather than just individual fraud.

The Road Ahead

The ECI has opened a window for “Claims and Objections” from 16 December 2025 to 15 January 2026, allowing those deleted to apply for reinstatement. However, for the millions of “unmatched” voters facing hearings, the coming weeks promise anxiety and bureaucratic struggle.

Mamata Banerjee’s invocation of “ladles and rolling pins” is more than just political theatre; it is a signal that the administrative process of voter revision has morphed into a visceral struggle for civil rights.

To understand the situation facing Bengal’s voters, consider this analogy: The 2002 benchmark is like a bank suddenly demanding you produce a grocery receipt from twenty-three years ago to prove you own the money currently in your account. While the bank’s intention might be to prevent fraud, for the majority of honest customers who simply didn’t keep the receipt, the demand feels less like a security measure and more like an eviction notice.